When my mother first came to the US from Taiwan, she found the food here a little difficult to embrace. Except for spaghetti. Slurping up long, slippery strands of pasta was a familiar sensation that became the entry point for appreciating more American foods. Only spaghetti wasn’t exactly all-American. Or it wasn’t considered so then, at least. But now today, more and more Americans are slurping up bowls of Asian noodle soups, from soba to ramen to pho.

What is American food if not a best-of list of beloved traditions of “old worlds” passed down by immigrants? Sure, there are many other reasons why ethnic foods are popularized in a country where it is not native—colonization, in the case of the curry being a staple dish in Britain, for example. Or slavery. Or a celebrity chef popularizing XYZ cuisine. But in America, immigration is the primary reason we have so many cuisines making up the fabric of our food culture, and it continues to evolve through new waves of people. I thought it was an especially proud time to share that heritage through a recipe or blog post related to immigration, in response to the current political landscape and the President’s executive order(s) on immigration. Because there are many things that unite us as a nation of immigrants. But our food is so tasty, it must be one of the greatest unifiers of them all.

And let’s be real: what’s one food that kids always like? Noodles. Macaroni, instant ramen, spaghetti, chicken noodle soup, you name it. There is something irresistible about a big tangle of pliant, chewy threads of dough soaked in tasty sauces. It is hard not to like noodles. I also find it hard to think of a noodle that isn’t tied to a unique group of immigrants in the US. From the kugel casseroles of Jewish American families to the pastas of Italian Americans and the noodle soups and stir-fries of Asian Americans, is there a noodle that you can’t call “ethnic” in some way? Even the dried egg noodles found in grocery store aisles are often emblazoned with Pennsylvania Dutch branding, and the German word “knudel” is its etymological mother. That might not “sound” too ethnic, but let’s remember that many of those Pennsylvania Dutch settlers came to the States looking for religious freedom not found in their home countries, and were totally weird outsiders in their new home. In other words, they were freaky immigrants.

(Side note, I recently tried my hand at making spaetzle, a truly lovable type of noodle. I couldn’t figure out how it was supposed to be made from written directions until watching this video of a German grandma do it so skillfully over a boiling pot of water. Highly recommended fun cooking challenge, especially if you’ve already mastered fresh pasta.)

Sometimes we become so enthralled by the latest food trends or the next unexplored dish that we often forget that some of the best recipes lie in our own family tree. I’d never thought before to share a recipe for zha cai rou si mian (Pickled Vegetable and Slivered Pork Noodles)—or even make it for anyone outside my family. But it’s a favorite that my mother made often when I was growing up, and still does.

It’s a very simple noodle soup, involving slivered pork tossed with slivers of pickles to top a bowl of noodle soup. Only the pickles in question (zha cai) are crunchy strips of pressed, fermented stems of a certain type of mustard greens that I can never find fresh anywhere in the States. I don’t think too many people pickle it themselves from the fresh plant, either. Growing up, there was always a half-used can of these in the fridge, dipped into regularly for using in this noodle soup or stir-fries. Or, to pick some out with my fingers and eat stealthily straight from the can.

I developed a recipe for a similar type of lacto-fermented pickle in The Food of Taiwan, this one using the base of a mustard green bunch. The process is simple, and it’s just like making sauerkraut or kimchi (without the spices). It’s essentially salted and left to ferment in its own salty liquids about a week until pungent. I’ve been making sauerkraut lately, using up half-heads of cabbage and lacto-fermenting them with purely salt and its own juices in a jar. So when I had a craving for zha cai rou si mian I wondered if the similarly funky, lacto-fermented cabbage (sauerkraut) would be an apt substitute for zha cai to toss along with the shredded pork. Turns out it did the trick just great.

And I’m sharing it now, for my #ImmigrationIsTasty post. I’ve been much too remiss to share authentic and esoteric Chinese or Taiwanese recipes on this blog. I mostly stuck with dishes that most Americans had already heard of, opting for chicken or beef, or ingredients popular in this country and for this audience. I’m not sure why anymore. It’s about time we brought more of the favorites out of the immigrant closet, because if I think it’s really good, then chances are other people will, too. No matter if they’ve seen it before or not. That’s how we develop a cuisine after all, and that’s how we always have.

Zha Cai Rou Si Mian with Pickled Cabbage (Sauerkraut) instead of Zha Cai

(makes 2 servings)

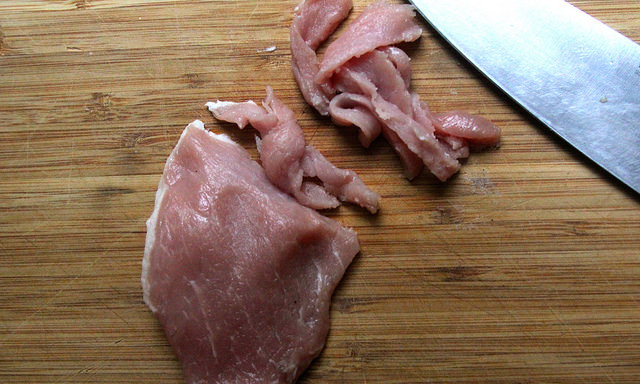

1/2 lb pork shoulder or tenderloin, sliced to thin strips against the grain

1/2 teaspoon cornstarch

1 teaspoon soy sauce

1 teaspoon sesame oil

dash of salt and white pepper

2 bundles Asian wheat noodles (can be dried or fresh, egg or non-egg, whichever thickness you like)

1 tablespoon neutral oil (such as vegetable or peanut)

for the soup:

4 cups chicken or pork stock (preferably homemade)

2 teaspoons sha-cha sauce (optional, or substitute with another type of chili sauce)

1 cup sauerkraut (or zha cai if you have it, or cut up some kimchi into slivers)

2 scallions, chopped (optional)

soy sauce to taste

Combine the pork with the cornstarch, soy sauce, sesame oil and a pinch each of salt and white pepper. Let marinate at least 20 minutes or up to 1 day in the refrigerator.

Cook the noodles according to the instructions on the package. Meanwhile, heat the tablespoon of neutral oil in a saucepan or wok. Once hot and sizzling, add the marinated pork and stir immediately to break up. Continue to cook until just lightly browned and thoroughly cooked through, about 2 minutes. Remove from heat.

Drain the noodles once cooked. In another pot, bring the stock to a boil. Divide hot stock into 2 noodle bowls and stir in the optional sha-cha sauce or chili sauce. Taste and add soy sauce to taste. Divide the cooked noodles amongst the two bowls, and top each with half the cooked pork, sauerkraut or pickled vegetables, and chopped scallions. Serve immediately.

Cost Calculator

(for 2 servings)

2 bundles Asian noodles: $0.50

1/2 lb pork tenderloin: $2.00

1 cup homemade sauerkraut: $0.50

4 cups homemade chicken stock: $1.00

2 scallions: $0.25

2 teaspoons sha-cha sauce: $0.50

2-3 teaspoons soy sauce and 1 teaspoon sesame oil: $0.25

salt, white pepper, 1/2 teaspoon cornstarch, 1 tablespoon neutral oil: $0.25

Total: $5.25

Health Factor![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Five brownie points: This is a cozy, cold-weather-perfect comfort food much like homemade chicken noodle soup. It gets extra points in both flavor and health benefits for the lacto-fermented cabbage, which has probiotic qualities in addition to all the nutrients found in that cabbage to begin with. That should help you digest and balance out the fatty pork and carb-y noodles.

Green Factor

Six maple leaves: Even though it’s a meat-based noodle soup, it has an even ratio of pork to vegetables as a topping, and it’s a typically great way to use leftover bits or scraps of pork. (Instead of pork, I made another bowl of this same noodle soup topped with leftover shreds of roast chicken, the same chicken that the stock was made with as well.) So use what you have, and when possible, pickle your own cabbage or other seasonal vegetables instead of buying canned. It’ll save those unused scraps of veggies from going to the trash, as well as be a fun project or stand-in for your favorite ethnic pickled vegetable, as it were.

7 Responses

instagram online

I have never tried Zha Cai Rou Si Mian, thank you for the recipe! The dried noodles looks so big 😮